Another round of belt tightening

We look at the key points of the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ newly-published report on education funding, including the impact on the estate

New estimates by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) find that the 2.8% cash-terms growth in mainstream school funding per pupil in England in 2025-26 will not be sufficient to cover the expected increase in school costs, currently predicted to be around 3.6%.

And there are fears that capital spending will be less than expected moving forward, leading to plans for improvements to the estate being pared back at a time when backlog maintenance and RAAC costs are growing.

The figures are outlined in Annual report on education spending in England: 2024–25 by researchers at the IFS, published on 8 January and funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

Luke Sibieta, IFS research fellow and report author, said: “This year’s spending review will bring a lot of difficult choices on education funding in England.

“A very-tight picture on the public finances means that most departments, including education, will probably need to make savings.

“Working out exactly how, and where, is much easier said than done.

“Spiralling costs of special educational needs provision seem likely to wipe out any opportunities for savings in the schools’ budget from falling pupil numbers.

“College and sixth form budgets are already stretched, and will need to cover the cost of rising student numbers.

“The inflation-linked rise in tuition fees only provided a brief reprieve for university finances, and further tuition fee rises seem likely.”

Spiralling costs of special educational needs provision seem likely to wipe out any opportunities for savings in the schools’ budget from falling pupil numbers

Josh Hillman, director of Education at the Nuffield Foundation, added: “Amid a tough fiscal climate and competing priorities, the IFS’s annual report delivers essential, independent analysis of the winners and losers in education spending.

“The analysis outlines the complex web of factors influencing the Government’s decision-making on funding for the early years, school pupils, and further and higher education students.

“And it highlights a range of challenges suggesting that the spending squeeze for schools and colleges will continue, but some gains for the under-5s.”

Number crunching

Between 2019-2024, total school spending in England grew by about £8bn. This led to 11% real-terms growth in school spending per pupil and fully reverses cuts since 2010.

But over half of the rise in school funding has been absorbed by rising costs of SEN.

After accounting for planned spending on high needs (which is a statutory requirement), the IFS estimates that mainstream school funding per pupil grew by 5% in real terms between 2019-2024, rather than the 11% total increase.

With pupil numbers expected to fall by 2% between 2025-2027, the Government could make annual savings of up to £1.2bn by freezing spending per pupil in real terms.

However, the Government also projects high needs spending will grow by £2.3bn between now and 2027 without reforms.

This makes finding savings in the schools budget impossible without cutting mainstream per-pupil spending in real terms.

Winners and losers

Early years is set for the biggest ever increasing in funding.

From September 2025, all children in working families will be entitled to up to 30 hours of funded childcare a week from nine months old.

As a result, spending on the free entitlement will rise to £8.5bn in 2026-27 from £4.2bn in 2023-24 and £2.2bn in 2010-11.

Spending on colleges and sixth forms remains well below 2010 levels, and pressures are growing.

Even with recent funding increases, the IFS estimates that college funding per student aged 16-18 in 2025 will still be about 11% below 2010 levels, and about 23% lower for school sixth forms.

About 37% of colleges were operating deficits at the latest count (2022–23).

Average college teacher pay is expected to be about 18% lower than pay for school teachers in 2025, contributing to the high exit rates among college teachers (with 16% leaving their jobs each year).

Meanwhile the number of young people in colleges and sixth forms is expected to grow by 5% or over 60,000 between 2024-2028.

Schools and colleges have been expected to absorb relentless financial pressures over the past 15 years, and they have done an incredible job in minimising the impact on students. But we cannot go on like this. It is death by a thousand cuts. The Government must recognise the importance of improved investment in education

The Government would need to increase annual funding by £200m in 2027-28 in today’s prices to maintain spending per student in real terms.

Increasing tuition fees in line with inflation will provide only slight reprieve for university finances after more than a decade of cash-terms freezes.

International student numbers are likely to have fallen in 2024-25, and the rise in employer national insurance contributions will increase staff costs from April 2025.

Unlike schools and colleges, universities are not being compensated for this increase.

Meanwhile, in 2025 the poorest students will be entitled to borrow 10% less in real terms than in 2020 to cover their maintenance costs.

Speaking to Education Property following the release of the report, Julie McCulloch, director of policy at the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “This report reveals the reality that is facing many schools and colleges – yet another round of cutbacks.

“It will inevitably mean further reductions to pastoral support, curriculum options and classroom resources.

“It is also likely that in many cases class sizes will increase.

“Schools and colleges have been expected to absorb relentless financial pressures over the past 15 years, and they have done an incredible job in minimising the impact on students.

“But we cannot go on like this. It is death by a thousand cuts. The Government must recognise the importance of improved investment in education.”

Daniel Kebede, general secretary of the National Education Union, adds: “Schools have no capacity to make savings without cutting educational provision.

“Britain has the highest primary class sizes in Europe and the highest secondary class sizes since records began and college funding has been cut to the bone.

“Funding for SEND support and pastoral care is totally inadequate and children and young people’s education has been seriously compromised through a lack of funding.

We are determined to fix the foundations of the education system that we inherited and will work with schools and local authorities to ensure there is a fair education funding system that directs public money to where it is needed to help children achieve and thrive

“The Government must address this problem head on and ensure that our schools and colleges get the funding they desperately need.”

Following publication of the report a Department for Education spokesperson said: “One of the missions of our plan for change is to give children the best start to life.

“This was built upon the steps set out at the Budget which increased school funding to almost £63.9bn in financial year 2025-26, including £1bn for children and young people with high needs.

“We are determined to fix the foundations of the education system that we inherited and will work with schools and local authorities to ensure there is a fair education funding system that directs public money to where it is needed to help children achieve and thrive.”

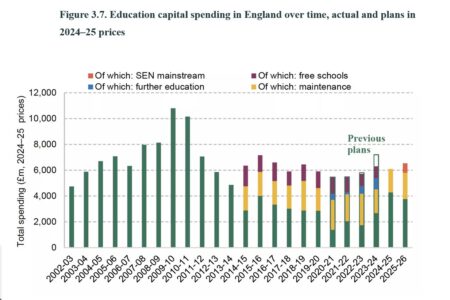

Source: HM Treasury Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses

Estates spending

The report considers capital spending on school buildings and maintenance.

It shows that total capital spending on education in England was about £6.3bn in 2023–24. This reflects different types of capital spending.

In 2023-24, about £1.8bn was devoted to school maintenance and repair, £900m was spent on free schools, and £900m was spent on rebuilding further education colleges, with about £2.7bn on new schools and other aspects of capital spending.

Interestingly, though, the actual level of capital spending seems to be about £900m less than previous plans from a year ago and this is likely to reflect the significant delays in the school rebuilding programme.

Money for these delayed projects will either need to come out of allocations from 2024-5 onwards, or the plans will need to be scaled back, says the report.

The Government also faces the cost of addressing RAAC in schools.

To date, the Government has provided schools with support through two main mechanisms.

Firstly, some schools have received grants for repairs and works – totalling £181m in 2023–24 – with further grants in future years.

Secondly, some costs will be met through the school rebuilding programme, given the scale of the work required.

For 2024-25, government plans still imply spending of about £6.1bn, matching previous plans.

And, in the Autumn Budget 2024, the Government set out education capital spending plans of £6.5bn for 2025-26.

From this amount, the Government has already committed to about £2.1bn for school maintenance (about equal to the average real-terms spending over the past decade). It has also committed £740m to help mainstream schools adapt infrastructure to expand core provision for SEND.

This leaves about £3.8bn, which will need to cover school and college rebuilding projects, the costs of addressing RAAC, as well as any other capital plans.

The report states: “As can be seen, capital spending tends to be lumpy over time.

“There was a large increase in spending in the late 2000s, with spending increasing from nearly £7bn in the mid-2000s to over £10bn in 2009-10 and 2010-11 (all in today’s prices).

“The large increase reflects the last Labour Government’s Building Schools for the Future programme, with delays in this programme leading to the big upticks in spending in 2009-10 and 2010-11.

“There was then a large decline up to 2013-14. Since then, overall capital spending has oscillated around £6bn-7bn per year in today’s prices.

“Plans for 2025-26 remain well within this range and thus not significantly different from experience over the last decade.

“Furthermore, the fact that plans include further education college rebuilding may mean the underlying level of school capital spending is lower than over the past decade.

“The planned level of education capital spending is also similar to the level last seen in the mid-2000s.

The big question

“The big question is whether spending is meeting current needs.

“National Audit Office (2023) reported that the Department for Education calculated it needed about £5bn per year from 2021 to 2025 in order to maintain school buildings and mitigate the most serious risks.

“This was based on a survey of the condition of school buildings. It instead requested about £4bn per year based on the rate at which it could increase spending.

“HM Treasury allocated about £3bn per year. As a result, actual funding allocations from government have been more than 40% below government-assessed levels of need.

“For 2025–26, school maintenance spending is due to be about £2.1bn, which is about 13% higher than in 2024-25, but still about the same level in real terms as the average over the past decade.

“This strongly suggests that school maintenance spending remains well below government-assessed levels of need.

“In summary, spending on school buildings is relatively low in historical terms and low compared with levels of need for maintenance and repair.”

Based on the analysis of the National Audit Office and Department for Education, there is a strong case for increasing spending on school buildings.

With a small drop in the pupil population over the next few years, there might be some scope to redirect funding from new schools towards repairs and maintenance.

In the Autumn Budget 2024, the Government chose to top-up capital spending allocations for future years, particularly 2025-26. However, total capital spending across departments is only expected to rise by 3% in real terms in 2026-27 and is due to be frozen in real terms in 2027-28. This suggests little scope for further significant increases in school maintenance spending over the next two-year spending review period.